by

Paul Bucci

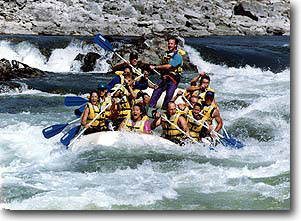

I remember thinking that I'd really like to see that country again. So when I heard that Bernie Fandrich at Kumsheen Raft Adventures was planning a six-day excursion down the Fraser River, I jumped at the chance to go. Kumsheen's rafts are the ultimate huge whitewater boats. They're giant rubber pontoon vessels with outriggers for additional flotation. In all, they have something like 18-tons of buoyancy. The Fraser is the heart and soul of British Columbia. This magnificent waterway runs 820 miles (1250 km) from the upper Rocky Mountains to Vancouver, where its incredible power changes the colour of water some say 15 kilometres into the Strait of Georgia. During the spring flood, the river has a volume of up to 500,000 cubic feet per second, which rivals the flow of the Mississippi River. Kumsheen's six-day Fraser and Thompson rivers excursion starts at the tiny village of Soda Creek. These few houses were once part of a thriving community where steamships picked up cargo and people from the northern most point of the railway. Long stretches of the Fraser still look today much as it did in 1808 when Simon Fraser and his group of explorers first cautiously paddled their way down the upper Fraser's 36 sets of rapids. But unlike today, Simon Fraser had no real idea where he was, and his canoes were really not up to the trip. Kumsheen's trip leader Adam Forseth had painstakignly briefed his modern day voyagers on what to do if you fell out of a raft, or if the vessel flipped, or what to do if, say, you were sucked down a horrible gaping whirlpool. Simon Fraser didn't have the luxury of a safety briefing and after just two days on the river, he'd decided that the route would never be a trade corridor. Kumsheen's rafts, with a 30-hp outboard for steerage floated effortlessly over rapids that had caused fear and trepidation in Simon Fraser and his crew.

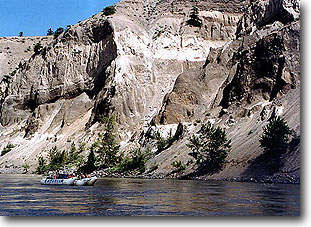

"The river had already driven the fear of the Lord into him when he got there," said Bernie, as his raft floated on the Fraser's turgid brown waters while towering mountains, sandstone cliffs and oddly shaped "hoodoos" passed by. We came to portage du baril where the river narrowed into a canyon with tall hills on either side. While the guides huddled in the back of the raft to discuss their strategy for going through the rapids, Bernie read from Simon Fraser's journal: "Here we unloaded on the left side of strong rapid," Fraser wrote. "Incredible it is to relate the trouble and misery the people had performing that office." "The river here does not exceed 30 yards in breadth, passes between two precipuses, and is turbulent, noisy and awful to behold." The extreme turbulence was caused by a constriction rapid, where the already surging river -- already moving at about 15 kmh -- is squeezed into a narrow waterway surrounded by cliffs. Boulders on the riverbed cause the river to heave, canyon walls force the water, moving at about 150,000 cubic-feet per second, to crash back on itself, reversing the river's direction in places. This creates huge surges, standing waves and whirlpools that suddenly open. The guides planned their path through the canyon, hollered hang on, and pointed their bows through the gorge. The water roared past huge black rocks and the engine whined as the guide bucked and surged down the cataract. Suddenly, as the boat slipped off the side of a standing wave, a vicious back current ripped into the raft, and I could feel the river try its best to flip all 18-tons of Kumsheen buoyancy into the water. With a violent shudder, the raft bucked over the hazard. Heart pumping, I looked back at guide Lochie Mackenzie. "Quite a trip, eh," he said, smiling calmly as the wind whipped his hair. I could see why Simon Fraser had his men heave his boats and gear over the canyon's cliffs. He rewarded them with a keg of green rum. And that's how this canyon got its name, which translates to portage of the barrel.

The river is brown, laden with gold and other bits of dust eroded from its shores and hundreds of feeder creeks. Deer dot the riverside, as do bears, eagles and all sorts of other animals. Old mines and abandoned miners' huts, along with homesteader's cabins and other shacks speak of dozens of dreams gone by. Huge rocks spire into the sky. Tall mountains with sweeping striations look just as grand as the Grand Canyon. Big horn sheep eke out a living in in the area of the Gang Ranch and the Empire Valley Ranch, hiding behind clay and rock pillars hundreds of feet high. Amid this breath-taking grandeur, Simon Fraser's last big test was rapide du couvert, which is known as French Bar Canyon today. I'd been on the river a few days, eating Kumsheen's gourmet food, and, like a piker, using all of their comfortable camping gear and tents. We camped a few miles upriver from these rapids. Contrary to Kumsheen's rules (thou shalt not booze while rafting,) I brought out a bottle of scotch and poured the river a small libation. Then I libated myself.

Nearly 200 years ago, Simon Fraser had been warned about French Bar Canyon, but, like me, his confidence in his ability to handle the river was growing. "Here is an amazing strong rapid which is the one called le rapide couvert, so long talked of," Fraser wrote. "The rocks contract themselves to within a very short distance of one another, and is the narrowest place we have yet passed, and the rocks above project themselves still farther out and the water between passes with the greatest velocity of anything I ever saw and the waves are high...This is the most most dangerous place we've hitherto passed." The river gods are fickle. And so, despite my worry and Simon Fraser's concern those many years ago, we both made it through the canyon with no ill effect. But unlike Fraser, who cached his canoes and food and walked down river not far after French Bar, I rafted to Lytton and then spent a day rafting on the Thompson River. I had the luxury of enjoying the view, travelling with expert guides, and being pampered beyond belief. Simon Fraser was greeted by hostile natives near the mouth of the Fraser. He discovered to his frustration that he wasn't at the mouth of the Columbia River. He turned tail and struggled all the way back up the waterway that would eventually bear his name to where the Nechako river enters the Fraser. Simon Fraser, by the way, died penniless, even though he canoed on a river with millions of dollars in gold deposits. In contrast to Fraser, I spent my last night at Kumsheen relaxing in the resort's hot tub. Like I said, the river gods are fickle.

|