Scuds, a Stillwater Staple

with

Philip Rowley

Website

| Email

I had anchored in six feet of water. Cruising within eye shot were pods

of trout ranging from 2 to 4 pounds. Every once in a while one would dart

suddenly to pick off some unseen food source. Suppressing the urge to beat

the water to a froth I continued my observations. Sitting quietly in my

boat fish would cruise right up to and beneath my boat. I could see the

wink of the trout's white mouth as it fed but could not see what they were

taking. About 20 feet away I observed one trout tip up and root his nose

around in the marl. This created a small mushroom cloud of silt and debris.

The trout wheeled about and began foraging amongst the debris. This commotion

brought other trout into the fray. Unable to watch any longer I tied on

a small scud pattern and cast it well ahead of a pod of fish. I had decided

upon the scud pattern as there was no observable hatch taking place. The

trout were feeding on some small food item I thought a scud might be the

likely culprit. Painstakingly I allowed the pattern to sink. It was hard

not to start cranking the pattern right away. After 10 seconds or so I

began a slow hand twist retrieve. Every once in a while I would mix in

a quick 3 to 4 inch strip in the hopes of drawing the interest of a feeding

trout. A couple of casts later my line tightened as though I had hung up

on the bottom. Just to be sure I lifted my rod. The water erupted in spray

and airborne trout. Seeking the security of deeper water the rainbow

left the shallows at warp speed. I kept the rod tip high and began a kind

of jig to ensure I did not step on my fly line and break the fish off.

About 10 hard fought minutes later I slipped my landing net beneath a beautiful

3 lb. Kamloops

rainbow. I pumped the fish, removed my fly and began reviving the fish.

Rested and ready to fight another day the trout swam leisurely away from

my boat somewhat tired, hungry and a little wiser. The stomach pump contents

confirmed my suspicions, scuds, small Hyallela to be exact. trout were feeding on some small food item I thought a scud might be the

likely culprit. Painstakingly I allowed the pattern to sink. It was hard

not to start cranking the pattern right away. After 10 seconds or so I

began a slow hand twist retrieve. Every once in a while I would mix in

a quick 3 to 4 inch strip in the hopes of drawing the interest of a feeding

trout. A couple of casts later my line tightened as though I had hung up

on the bottom. Just to be sure I lifted my rod. The water erupted in spray

and airborne trout. Seeking the security of deeper water the rainbow

left the shallows at warp speed. I kept the rod tip high and began a kind

of jig to ensure I did not step on my fly line and break the fish off.

About 10 hard fought minutes later I slipped my landing net beneath a beautiful

3 lb. Kamloops

rainbow. I pumped the fish, removed my fly and began reviving the fish.

Rested and ready to fight another day the trout swam leisurely away from

my boat somewhat tired, hungry and a little wiser. The stomach pump contents

confirmed my suspicions, scuds, small Hyallela to be exact.

Scuds

are one of the most overlooked items on the trout's menu. In the nutrient

rich waters of British Columbia and the western United States scuds

are second only in importance to Chironomids.

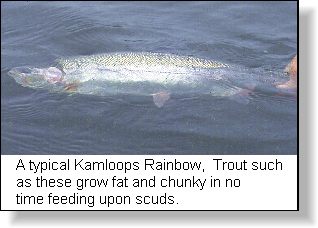

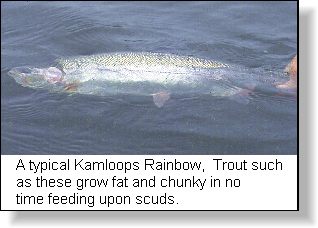

Scuds' compromise over 20% of the trout's food intake. Scuds are one

of the staples in any lake as they are available to the trout year round.

The scud is especially important in the early spring or late fall prior

to ice on. Yet like the chironomid, scuds do not seem to get the attention

they deserve. Lakes that contain good quantities of scuds grow large,

fat trout. A consistent diet of scuds leads to phenomenal growth rates

of over 1.5 lb. per season or greater. Scuds

are one of the most overlooked items on the trout's menu. In the nutrient

rich waters of British Columbia and the western United States scuds

are second only in importance to Chironomids.

Scuds' compromise over 20% of the trout's food intake. Scuds are one

of the staples in any lake as they are available to the trout year round.

The scud is especially important in the early spring or late fall prior

to ice on. Yet like the chironomid, scuds do not seem to get the attention

they deserve. Lakes that contain good quantities of scuds grow large,

fat trout. A consistent diet of scuds leads to phenomenal growth rates

of over 1.5 lb. per season or greater.

LIFE CYCLE OF THE SCUD

Scuds are members of the class Crustacea, order Amphipoda. Scuds'

are distant cousins to the crayfish, sowbugs and shrimp.

Many fly fishers actually use the term shrimp when referring to scuds.

Upon closer look however scuds differ markedly from these distant cousins.

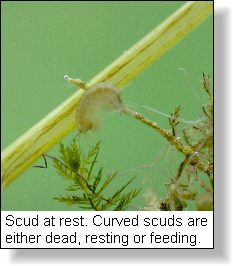

Scuds have a distinct armadillo like appearance. They have a hard, segmented

exoskeleton and 7 pairs of legs carried underneath the body. The front

2 pairs of legs serve for grasping while the remainder serve as locomotion.

These legs enable the scud to swim quickly at times, although they commonly

move in an erratic and random manner. Some species prefer moving around

in an upside down fashion. Scuds also have 2 pairs of antenna that extend

roughly half the length of the body. Located between the various pairs

of legs are their gills. Scuds spend their entire life beneath the water's

surface. There is no pupal stage or emergence of any kind. Scuds are prolific.

Densities of over 10,000 per square yard are not uncommon on some lakes

and ponds. One mating pair of scuds can produce upwards of 7 broods, totaling

20,000 offspring per year under ideal conditions. Scuds mate in a piggyback

like fashion with the female usually on top. They are omnivorous feeders,

dining on just about anything. I have seen scuds attack larger organisms

such as damsel fly nymphs and water boatmen in Piranha like fashion, yet

they seem to prefer a vegetarian diet.

There

are 2 species of scuds that the fly fisher needs to be aware of. These

are Gammarus and the smaller Hyalella. There are eight genera of Gammarus.

The two most common are, Gammarus Fasciatus and Gammarus Lacustris.

Hyalella Azteca is the most widespread among the Hyalella genera. Of

the two species the Hyalella is more widespread. Gammarus need alkaline

waters rich in calcium to generate large populations. Calcium is a requirement

for Gammarus to form their chitinous exoskeletons. A good rule of thumb

to determine the alkalinity of a lake is by the water clarity. Alkaline

lakes tend to be clearer bodies of water with light marl bottoms and

good growths of green Chara weed. Acidic lakes on the other hand tend

to be darker in color and lily pads may be prevalent. The Gammarus scuds

are larger in size than Hyalella. Gammarus can attain sizes of up to

3/4 of an inch, while the smaller Hyalella seldom exceed 1/3 of an inch. There

are 2 species of scuds that the fly fisher needs to be aware of. These

are Gammarus and the smaller Hyalella. There are eight genera of Gammarus.

The two most common are, Gammarus Fasciatus and Gammarus Lacustris.

Hyalella Azteca is the most widespread among the Hyalella genera. Of

the two species the Hyalella is more widespread. Gammarus need alkaline

waters rich in calcium to generate large populations. Calcium is a requirement

for Gammarus to form their chitinous exoskeletons. A good rule of thumb

to determine the alkalinity of a lake is by the water clarity. Alkaline

lakes tend to be clearer bodies of water with light marl bottoms and

good growths of green Chara weed. Acidic lakes on the other hand tend

to be darker in color and lily pads may be prevalent. The Gammarus scuds

are larger in size than Hyalella. Gammarus can attain sizes of up to

3/4 of an inch, while the smaller Hyalella seldom exceed 1/3 of an inch.

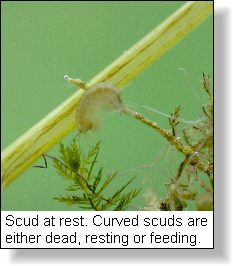

Regardless of the species scuds prefer to inhabit the shallow regions

of a lake. Scuds are capable in living in depths as great as 50 ft, but

prefer shallower depths of 15 ft or less. Scuds prefer to inhabit vegetation

such as Chara weed or Milfoil, but are quite at home under rocks and sunken

debris. Species such as Hyallela appear to prefer the light colored marl

bottom of a lake. Hyallela will bury themselves to avoid predators and

search for food. Scuds are light sensitive and are most active in low light

conditions. I have seen scuds take refuge from the light in large numbers

under boats and other shady areas. Overcast days can be good days to fish

a scud pattern.

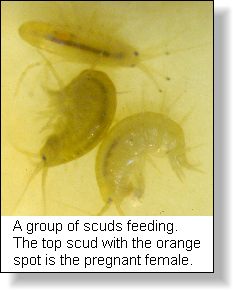

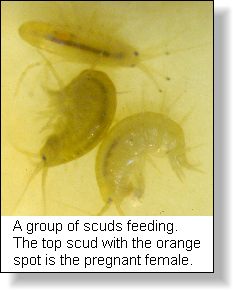

Scuds

are available in a wide range of colors. The most common colors include;

shades of green, olive, grey, yellow, and tan. I have even seen some

scuds that are a beautiful turquoise color. A good rule of thumb is,

darker the water the darker the coloration of the scuds. However the

translucent scud has a chameleon like quality. During times of low weed

growth the scuds will be pale in color. As the weeds grow, scuds are

able to change color to match their surroundings. Scuds lose the ability

to camouflage themselves effectively as they near the end of their lives.

The coloration tends to become various tones of yellow. Coloration can

also vary between species. The Hyallela species is generally lighter

in color than the larger Gammarus. From time to time anglers might observe

scuds with an orange colored spot in the middle of their body, these

are pregnant females. The orange spot is the brood pouch, or Marsupium.

At certain times' trout will key in on these pregnant scuds, so the

angler should have a few patterns tied that imitate this characteristic.

In some stomach samples you might see orange colored scuds. This is

not their natural color. When a scud dies the natural coloration disappears,

the orange color is due to the presence of Carotene. Carotene transfers

to the fish during the digestive process and leads to the beautiful

pink flesh that is typical of the Kamloops trout. Scuds

are available in a wide range of colors. The most common colors include;

shades of green, olive, grey, yellow, and tan. I have even seen some

scuds that are a beautiful turquoise color. A good rule of thumb is,

darker the water the darker the coloration of the scuds. However the

translucent scud has a chameleon like quality. During times of low weed

growth the scuds will be pale in color. As the weeds grow, scuds are

able to change color to match their surroundings. Scuds lose the ability

to camouflage themselves effectively as they near the end of their lives.

The coloration tends to become various tones of yellow. Coloration can

also vary between species. The Hyallela species is generally lighter

in color than the larger Gammarus. From time to time anglers might observe

scuds with an orange colored spot in the middle of their body, these

are pregnant females. The orange spot is the brood pouch, or Marsupium.

At certain times' trout will key in on these pregnant scuds, so the

angler should have a few patterns tied that imitate this characteristic.

In some stomach samples you might see orange colored scuds. This is

not their natural color. When a scud dies the natural coloration disappears,

the orange color is due to the presence of Carotene. Carotene transfers

to the fish during the digestive process and leads to the beautiful

pink flesh that is typical of the Kamloops trout.

PRESENTATION PRESENTATION

Fly fishing with scud patterns is straight forward. I try to present

my patterns either on or near the bottom. Any type of fly line will do.

I prefer either an intermediate, the clear Stillwater line or a floating

line coupled with a long leader. By long leader I mean from 15 to 20 feet

depending upon the depth. Fishing a weighted scud pattern on a dry line

and a long leader is a favorite method of mine. It is much like chironomid

fishing. The intermediate or Stillwater lines give you a horizontal presentation

yet enable a slow enough retrieve to properly simulate the scud. For leaders

on the intermediate I use 9 to 12 foot leaders depending upon the water

clarity. The clearer the water the longer the leader.

As for retrieves it is tough to beat the old reliable hand twist retrieve.

At times a slow 10 to 12 inch strip retrieve can work well. Strip the

line and wait 2 to 3 seconds or more before stripping again. A brisk retrieve

can work well when the water temperature is up and fish are active. By

brisk I mean a choppy 3 to 4 inch strip retrieve, but don't over do things.

I use this basic rule the colder the water, the slower the fishing the

slower the retrieve. For inactive fish retrieves have to be slow and methodical

to be successful. It is easy to fall into the, "rip and strip"

method if for no other reason to keep warm and active. Not to many food

sources' trout feed upon in lakes move quickly even if they have the capability.

If an angler were to fish scuds and nothing else he or she would be successful

year round. The poor scud is like the Rodney Dangerfield of food sources.

It gets no respect. I know trout respect them and when nothing else is

moving or hatching. Being a stillwater staple trout seldom turn scuds down.

Pearl Shrimp Pearl Shrimp

Hook: Tiemco 2457 or 3769 #10-#16

Thread: Olive 6/0 or 8/0

Rib: Fine Copper Wire

Shellback: Pearlescent Sheet Material (found in many craft stores)

Body: Seals' Fur or Suitable Substitute (Color to suit)

Notes: Tie the shellback material in so that it protrudes out over the eye

of the hook. Once the body is complete pull the shellback material down

over the back of the fly. Wind the rib material to secure the shellback

in place. Trim the shellback even with the bend of the hook to form the

telsun of the scud.

Philip Rowley

|

trout were feeding on some small food item I thought a scud might be the

likely culprit. Painstakingly I allowed the pattern to sink. It was hard

not to start cranking the pattern right away. After 10 seconds or so I

began a slow hand twist retrieve. Every once in a while I would mix in

a quick 3 to 4 inch strip in the hopes of drawing the interest of a feeding

trout. A couple of casts later my line tightened as though I had hung up

on the bottom. Just to be sure I lifted my rod. The water erupted in spray

and airborne trout. Seeking the security of deeper water the

trout were feeding on some small food item I thought a scud might be the

likely culprit. Painstakingly I allowed the pattern to sink. It was hard

not to start cranking the pattern right away. After 10 seconds or so I

began a slow hand twist retrieve. Every once in a while I would mix in

a quick 3 to 4 inch strip in the hopes of drawing the interest of a feeding

trout. A couple of casts later my line tightened as though I had hung up

on the bottom. Just to be sure I lifted my rod. The water erupted in spray

and airborne trout. Seeking the security of deeper water the  Scuds

are one of the most overlooked items on the trout's menu. In the nutrient

rich waters of British Columbia and the western United States scuds

are second only in importance to

Scuds

are one of the most overlooked items on the trout's menu. In the nutrient

rich waters of British Columbia and the western United States scuds

are second only in importance to  There

are 2 species of scuds that the fly fisher needs to be aware of. These

are Gammarus and the smaller Hyalella. There are eight genera of Gammarus.

The two most common are, Gammarus Fasciatus and Gammarus Lacustris.

Hyalella Azteca is the most widespread among the Hyalella genera. Of

the two species the Hyalella is more widespread. Gammarus need alkaline

waters rich in calcium to generate large populations. Calcium is a requirement

for Gammarus to form their chitinous exoskeletons. A good rule of thumb

to determine the alkalinity of a lake is by the water clarity. Alkaline

lakes tend to be clearer bodies of water with light marl bottoms and

good growths of green Chara weed. Acidic lakes on the other hand tend

to be darker in color and lily pads may be prevalent. The Gammarus scuds

are larger in size than Hyalella. Gammarus can attain sizes of up to

3/4 of an inch, while the smaller Hyalella seldom exceed 1/3 of an inch.

There

are 2 species of scuds that the fly fisher needs to be aware of. These

are Gammarus and the smaller Hyalella. There are eight genera of Gammarus.

The two most common are, Gammarus Fasciatus and Gammarus Lacustris.

Hyalella Azteca is the most widespread among the Hyalella genera. Of

the two species the Hyalella is more widespread. Gammarus need alkaline

waters rich in calcium to generate large populations. Calcium is a requirement

for Gammarus to form their chitinous exoskeletons. A good rule of thumb

to determine the alkalinity of a lake is by the water clarity. Alkaline

lakes tend to be clearer bodies of water with light marl bottoms and

good growths of green Chara weed. Acidic lakes on the other hand tend

to be darker in color and lily pads may be prevalent. The Gammarus scuds

are larger in size than Hyalella. Gammarus can attain sizes of up to

3/4 of an inch, while the smaller Hyalella seldom exceed 1/3 of an inch. Scuds

are available in a wide range of colors. The most common colors include;

shades of green, olive, grey, yellow, and tan. I have even seen some

scuds that are a beautiful turquoise color. A good rule of thumb is,

darker the water the darker the coloration of the scuds. However the

translucent scud has a chameleon like quality. During times of low weed

growth the scuds will be pale in color. As the weeds grow, scuds are

able to change color to match their surroundings. Scuds lose the ability

to camouflage themselves effectively as they near the end of their lives.

The coloration tends to become various tones of yellow. Coloration can

also vary between species. The Hyallela species is generally lighter

in color than the larger Gammarus. From time to time anglers might observe

scuds with an orange colored spot in the middle of their body, these

are pregnant females. The orange spot is the brood pouch, or Marsupium.

At certain times' trout will key in on these pregnant scuds, so the

angler should have a few patterns tied that imitate this characteristic.

In some stomach samples you might see orange colored scuds. This is

not their natural color. When a scud dies the natural coloration disappears,

the orange color is due to the presence of Carotene. Carotene transfers

to the fish during the digestive process and leads to the beautiful

pink flesh that is typical of the Kamloops trout.

Scuds

are available in a wide range of colors. The most common colors include;

shades of green, olive, grey, yellow, and tan. I have even seen some

scuds that are a beautiful turquoise color. A good rule of thumb is,

darker the water the darker the coloration of the scuds. However the

translucent scud has a chameleon like quality. During times of low weed

growth the scuds will be pale in color. As the weeds grow, scuds are

able to change color to match their surroundings. Scuds lose the ability

to camouflage themselves effectively as they near the end of their lives.

The coloration tends to become various tones of yellow. Coloration can

also vary between species. The Hyallela species is generally lighter

in color than the larger Gammarus. From time to time anglers might observe

scuds with an orange colored spot in the middle of their body, these

are pregnant females. The orange spot is the brood pouch, or Marsupium.

At certain times' trout will key in on these pregnant scuds, so the

angler should have a few patterns tied that imitate this characteristic.

In some stomach samples you might see orange colored scuds. This is

not their natural color. When a scud dies the natural coloration disappears,

the orange color is due to the presence of Carotene. Carotene transfers

to the fish during the digestive process and leads to the beautiful

pink flesh that is typical of the Kamloops trout. PRESENTATION

PRESENTATION Pearl Shrimp

Pearl Shrimp