BC Outdoor Odyssey

Creeks = Salmon

with Barry M. Thornton

Wonderful things are happening in our creeks right now. Squirming

up through the gravel to greet the spring daylight are needle length silver

sided salmon. Some will still have a yolk sac extending from their belly

and these are still very shy. Others, however, will have a sleek salmon

shape where the yolk sac has receded to make the belly of the fish. These

salmon fry are hungry and within moments of having pushed up through the

gravel they will be drifted with the current to the tailout of pools. Here

the minute biomass of drifting surface material like leaf parts, blossoms, twigs and

flying insects becomes the staple foodstuff for their short and long stay

in freshwater.

Each of the five Pacific salmon species have an unique life story in their

fry stage, that period of time when they live in their natal stream. Chum

and pink salmon have evolved such that they remain in their natal stream

for only a short time, migrating downstream to the ocean almost from the

moment they struggle up through the stream bottom gravel. Chinook salmon

fry will remain in their natal river for a period of from one month to one

year. Sockeye salmon fry migrate upstream from where they hatch to remain

in a headwater lake for a period of one year. Coho and steelhead have the

most difficult freshwater stay. Coho remain in their natal stream for a

period of a year and a half before they migrate downstream to the ocean.

Steelhead trout, now classified as a salmon, have fry that remain in their

natal or home river for periods of two or three years. Some will remain up

to four years although this is rare. Each of the five Pacific salmon species have an unique life story in their

fry stage, that period of time when they live in their natal stream. Chum

and pink salmon have evolved such that they remain in their natal stream

for only a short time, migrating downstream to the ocean almost from the

moment they struggle up through the stream bottom gravel. Chinook salmon

fry will remain in their natal river for a period of from one month to one

year. Sockeye salmon fry migrate upstream from where they hatch to remain

in a headwater lake for a period of one year. Coho and steelhead have the

most difficult freshwater stay. Coho remain in their natal stream for a

period of a year and a half before they migrate downstream to the ocean.

Steelhead trout, now classified as a salmon, have fry that remain in their

natal or home river for periods of two or three years. Some will remain up

to four years although this is rare.

I have always enjoyed exploring streams during the spring of the

year. I recall a recent trip where, while wading a small tributary creek to

reach the main river for some steelhead fishing, I was startled by the

sudden swirl of water in front of me. There, only yards away, the upper

half of a square spotted tail sliced through the water like a shark fin.

When the large steelhead reached the deeper waters in the pool I could

still follow a surface "V" wake of water until the fish hid under a jam of

logs. May and June are a time when many steelhead spawn. I am certain that

I accidentally disturbed a pair on their spawning bed in the clean gravel

of this tributary creek. Their 6000 plus eggs will grow quickly as the

water temperature increases, and the fry will hatch out in late June or

early July. These steelhead fry will just have time to adapt to the

conditions in this creek before the summer drought will put a severe check

on their growth, such are the water fluctuations of our streams. But, they

have evolved for just such conditions and, when the water ceases to flow,

they will 'gravel-up' that is, they will burrow deep in the gravel of pools

and take on a summer hibernation state.

As my partner and I walked downstream beside the creek, we spotted

an eagle wing tangled in the branches of a riverside alder tree. The

deteriorating wing was at least two meters above the level of the creek,

obviously caught there during a winter high water flood. To think that this

tiny tributary was a raging river only recently was difficult to

conceptualize even though the evidence of branch limbs, snags, and

streambank high water mark pointed to the obvious. Then, to realize that

during late summer that this same bubbling creek would in most places be a

dry streambed was even more difficult to conceive. But, these extremes are

reality for our stream salmon. As my partner and I walked downstream beside the creek, we spotted

an eagle wing tangled in the branches of a riverside alder tree. The

deteriorating wing was at least two meters above the level of the creek,

obviously caught there during a winter high water flood. To think that this

tiny tributary was a raging river only recently was difficult to

conceptualize even though the evidence of branch limbs, snags, and

streambank high water mark pointed to the obvious. Then, to realize that

during late summer that this same bubbling creek would in most places be a

dry streambed was even more difficult to conceive. But, these extremes are

reality for our stream salmon.

Coho and creeks go together like boys and water. I am certain that

at one time all British Columbia creeks and streams with direct access to

the Pacific ocean (20,000+) held populations of coho, each unique to the

whims of that particular watershed. Unfortunately, habitat destruction has

seriously limited the number of creeks and watersheds that still retain

coho.

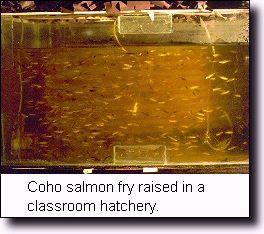

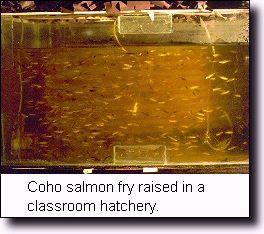

Coho eggs are laid in the late fall then hatch in early spring. The fry

remain in the creek for a year then leave the creek as a smolt during May.

Coho live in the ocean for a year and a half and then as 3+ kilo adults

they re-enter their home stream in November to spawn. All salmon except

steelhead die after spawning and contribute their body materials to the

ecosystem. This provides vital nutrients for the health of that watershed.

Coho watersheds have extensive networks of tributary creeks which

during high November flows often find spawning adults in strange

places. These adults will follow the flows of storm drains, ditches and

even culverts to reach spawning areas. It is a classic example of their

ability to find the greatest variety of nursery waters for their offspring.

Coho fry are the easiest of all salmon to identify as they often have

white tipped fins and no spots on their dorsal fin like trout. Take a quiet

walk along these creeks when the Trilliums, Fawn Lilies, Yellow violets and

Dogwoods bloom. Pause at the tailout of pools and look for moving shadows

on the creek bed. Once a fry is located it becomes easy to identify others

and, then, to clearly identify the coho fry. It is a special nature walk

that I highly recommend to all, a walk that brings a clear appreciation for

the adaptability of these unique fish, our Pacific salmon. Coho eggs are laid in the late fall then hatch in early spring. The fry

remain in the creek for a year then leave the creek as a smolt during May.

Coho live in the ocean for a year and a half and then as 3+ kilo adults

they re-enter their home stream in November to spawn. All salmon except

steelhead die after spawning and contribute their body materials to the

ecosystem. This provides vital nutrients for the health of that watershed.

Coho watersheds have extensive networks of tributary creeks which

during high November flows often find spawning adults in strange

places. These adults will follow the flows of storm drains, ditches and

even culverts to reach spawning areas. It is a classic example of their

ability to find the greatest variety of nursery waters for their offspring.

Coho fry are the easiest of all salmon to identify as they often have

white tipped fins and no spots on their dorsal fin like trout. Take a quiet

walk along these creeks when the Trilliums, Fawn Lilies, Yellow violets and

Dogwoods bloom. Pause at the tailout of pools and look for moving shadows

on the creek bed. Once a fry is located it becomes easy to identify others

and, then, to clearly identify the coho fry. It is a special nature walk

that I highly recommend to all, a walk that brings a clear appreciation for

the adaptability of these unique fish, our Pacific salmon.

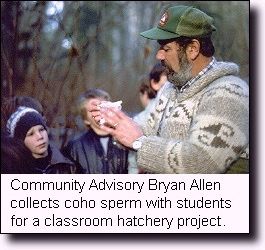

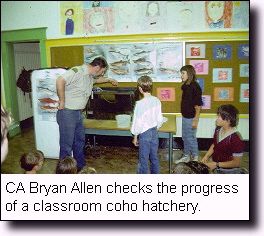

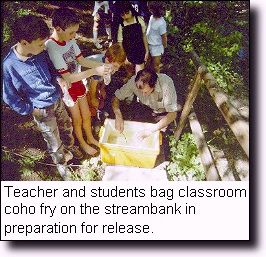

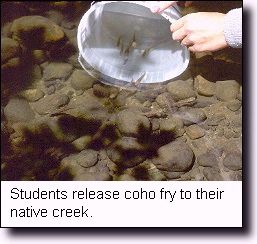

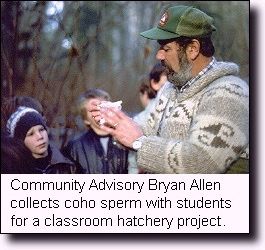

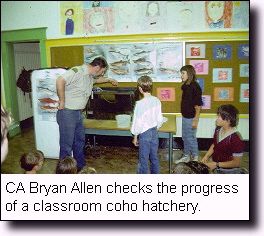

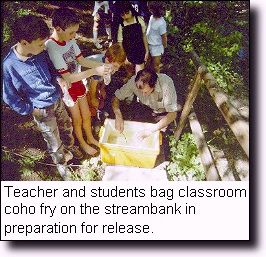

What can we do to protect these vital salmon nursery watersheds?

In 1996 Community projects and volunteers working through the Salmonid

Enhancement program released over 18,000,000 salmon fry in B.C. watersheds.

Throughout the province fifteen Community Advisors (CAs) of the Department

of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) coordinated these releases as well as school

and community hatchery projects, community habitat enhancement programs,

and various educational programs. What can we do to protect these vital salmon nursery watersheds?

In 1996 Community projects and volunteers working through the Salmonid

Enhancement program released over 18,000,000 salmon fry in B.C. watersheds.

Throughout the province fifteen Community Advisors (CAs) of the Department

of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) coordinated these releases as well as school

and community hatchery projects, community habitat enhancement programs,

and various educational programs.

For more information on how you can help, check the list

of Community Advisors and the B.C. map of the regions they represent, here.

© Copyright Barry M. Thornton

Barry M. Thornton

|

Each of the five Pacific salmon species have an unique life story in their

fry stage, that period of time when they live in their natal stream. Chum

and pink salmon have evolved such that they remain in their natal stream

for only a short time, migrating downstream to the ocean almost from the

moment they struggle up through the stream bottom gravel. Chinook salmon

fry will remain in their natal river for a period of from one month to one

year. Sockeye salmon fry migrate upstream from where they hatch to remain

in a headwater lake for a period of one year. Coho and steelhead have the

most difficult freshwater stay. Coho remain in their natal stream for a

period of a year and a half before they migrate downstream to the ocean.

Steelhead trout, now classified as a salmon, have fry that remain in their

natal or home river for periods of two or three years. Some will remain up

to four years although this is rare.

Each of the five Pacific salmon species have an unique life story in their

fry stage, that period of time when they live in their natal stream. Chum

and pink salmon have evolved such that they remain in their natal stream

for only a short time, migrating downstream to the ocean almost from the

moment they struggle up through the stream bottom gravel. Chinook salmon

fry will remain in their natal river for a period of from one month to one

year. Sockeye salmon fry migrate upstream from where they hatch to remain

in a headwater lake for a period of one year. Coho and steelhead have the

most difficult freshwater stay. Coho remain in their natal stream for a

period of a year and a half before they migrate downstream to the ocean.

Steelhead trout, now classified as a salmon, have fry that remain in their

natal or home river for periods of two or three years. Some will remain up

to four years although this is rare.

As my partner and I walked downstream beside the creek, we spotted

an eagle wing tangled in the branches of a riverside alder tree. The

deteriorating wing was at least two meters above the level of the creek,

obviously caught there during a winter high water flood. To think that this

tiny tributary was a raging river only recently was difficult to

conceptualize even though the evidence of branch limbs, snags, and

streambank high water mark pointed to the obvious. Then, to realize that

during late summer that this same bubbling creek would in most places be a

dry streambed was even more difficult to conceive. But, these extremes are

reality for our stream salmon.

As my partner and I walked downstream beside the creek, we spotted

an eagle wing tangled in the branches of a riverside alder tree. The

deteriorating wing was at least two meters above the level of the creek,

obviously caught there during a winter high water flood. To think that this

tiny tributary was a raging river only recently was difficult to

conceptualize even though the evidence of branch limbs, snags, and

streambank high water mark pointed to the obvious. Then, to realize that

during late summer that this same bubbling creek would in most places be a

dry streambed was even more difficult to conceive. But, these extremes are

reality for our stream salmon. Coho eggs are laid in the late fall then hatch in early spring. The fry

remain in the creek for a year then leave the creek as a smolt during May.

Coho live in the ocean for a year and a half and then as 3+ kilo adults

they re-enter their home stream in November to spawn. All salmon except

steelhead die after spawning and contribute their body materials to the

ecosystem. This provides vital nutrients for the health of that watershed.

Coho watersheds have extensive networks of tributary creeks which

during high November flows often find spawning adults in strange

places. These adults will follow the flows of storm drains, ditches and

even culverts to reach spawning areas. It is a classic example of their

ability to find the greatest variety of nursery waters for their offspring.

Coho fry are the easiest of all salmon to identify as they often have

white tipped fins and no spots on their dorsal fin like trout. Take a quiet

walk along these creeks when the Trilliums, Fawn Lilies, Yellow violets and

Dogwoods bloom. Pause at the tailout of pools and look for moving shadows

on the creek bed. Once a fry is located it becomes easy to identify others

and, then, to clearly identify the coho fry. It is a special nature walk

that I highly recommend to all, a walk that brings a clear appreciation for

the adaptability of these unique fish, our Pacific salmon.

Coho eggs are laid in the late fall then hatch in early spring. The fry

remain in the creek for a year then leave the creek as a smolt during May.

Coho live in the ocean for a year and a half and then as 3+ kilo adults

they re-enter their home stream in November to spawn. All salmon except

steelhead die after spawning and contribute their body materials to the

ecosystem. This provides vital nutrients for the health of that watershed.

Coho watersheds have extensive networks of tributary creeks which

during high November flows often find spawning adults in strange

places. These adults will follow the flows of storm drains, ditches and

even culverts to reach spawning areas. It is a classic example of their

ability to find the greatest variety of nursery waters for their offspring.

Coho fry are the easiest of all salmon to identify as they often have

white tipped fins and no spots on their dorsal fin like trout. Take a quiet

walk along these creeks when the Trilliums, Fawn Lilies, Yellow violets and

Dogwoods bloom. Pause at the tailout of pools and look for moving shadows

on the creek bed. Once a fry is located it becomes easy to identify others

and, then, to clearly identify the coho fry. It is a special nature walk

that I highly recommend to all, a walk that brings a clear appreciation for

the adaptability of these unique fish, our Pacific salmon. What can we do to protect these vital salmon nursery watersheds?

In 1996 Community projects and volunteers working through the Salmonid

Enhancement program released over 18,000,000 salmon fry in B.C. watersheds.

Throughout the province fifteen Community Advisors (CAs) of the Department

of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) coordinated these releases as well as school

and community hatchery projects, community habitat enhancement programs,

and various educational programs.

What can we do to protect these vital salmon nursery watersheds?

In 1996 Community projects and volunteers working through the Salmonid

Enhancement program released over 18,000,000 salmon fry in B.C. watersheds.

Throughout the province fifteen Community Advisors (CAs) of the Department

of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) coordinated these releases as well as school

and community hatchery projects, community habitat enhancement programs,

and various educational programs.