Steelhead fishing series

"Oncorhynchus mykiss - The Steelhead Trout"

with

Barry M. Thornton

|

|

|

Steelhead are the prized freshwater sports fish of British Columbia.

|

The Pacific coast of North America is home to one of the most exciting and challenging fresh water sports fish. The average weight of British Columbia's sports caught steelhead is eight pounds but, many have weights in the teens, the twenties, and even the thirties. These latter fish are the trophies that bring anglers from all over the world to fish British Columbia's 500 plus known steelhead streams.

The steelhead is a sea-going or anadromous species of rainbow (Kamloops) trout. Until the late 1980's it had the scientific name, Salmo gairdneri Richardson. However, the American Fisheries Society (AFS) recognized that the Kamchatka or Asian steelhead race had an historic previous label, mykiss, hence all steelhead and rainbow trout now have the name mykiss. At about that same time, the AFS determined that there was no biological reason for separating rainbow trout from Pacific salmon at the generic level. Therefore they labeled all trout and salmon of Pacific lineage in the same genus, Oncorhynchus. Today, steelhead throughout the world are known as Oncorhynchus mykiss.

|

|

|

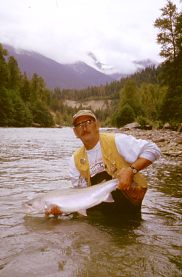

Releasing steelhead is the norm for most steelhead anglers.

|

My first experiences with the sporting thrill of steelhead occurred during the late sixties. I had moved to

Vancouver Island

and had the opportunity to fish 20 steelhead streams within a one hour drive from my home. I spent 12 months of the year on many of these streams, steelhead fishing, trout fishing, and snorkeling. My various diaries, both audio and written, tell of the thousands of encounters I was fortunate to have with this majestic fish in these and many other coastal rivers and streams. There is no doubt in my mind that the

steelhead

is the "Supreme Trophy Trout".

Steelhead have two distinct race, winter steelhead and summer steelhead, so named because of the season of the year these fish enter their home streams. Winter steelhead begin ascending their natal streams as early as November. Runs of these fish continue to ascend their rivers from November through April and some rivers actually have winter steelhead entering their systems as late as June. Summer steelhead begin to enter their home rivers in June and continue through October. Spawning for both races occurs throughout the winter months in fist sized gravel.

|

|

|

Fisheries staff electroshock a tributary stream to sample salmonids.

|

Temperature is the key factor which determines when the eggs hatch and when the yoke-bellied alevin break free to grow between the gravel. Once the young steelhead complete using their yoke food reserves they squirm up through the gravel and become free swimming fry. They live in their home stream for two, three, or even four years before they enter the smolt stage and migrate downstream to the ocean. Prior to reaching the ocean they 'silver-up' adapting to the osmotic change that will occur when their body moves from a fresh water environment to a salt water medium.

In the ocean steelhead migrate north along the continental shelf; then in a great eastern/southern crescent around the Gulf of Alaska; then, south along the shelf of the Aleutian Island chain to a vast marshaling ground near 50' N latitude and 170' W longitude. Here in this immense area of the Pacific ocean they mingle with steelhead from other North American streams and their Asian cousins from streams on the Kamchatka Peninsula. When the urge to migrate back to their home streams occurs they reverse their journey or make a direct line back to North American shores, then travel south until they reach the estuary of their home stream.

Steelhead are generally loners, fish that travel by themselves unless for opportunistic feeding times when they will find themselves in the company of other steelhead and salmon. When they reach the river mouth they will stay in the estuary until water conditions like a rain storm or freshet occurs which will draw them up the river. Once in the river they travel slowly, usually in the evening or early morning, or, during overcast days.

Some steelhead are wanderers, in fact nearly 20% wander to spawn in streams other then their home river. This wandering is the way that steelhead have historically populated streams and the manner in which genetic viability has occurred.

|

|

|

The larger fry captured while electrofishing are two year old steelhead.

|

Spawning is the ultimate purpose of all steelhead. It is their reason for being. Unlike Pacific salmon who die after spawning, steelhead are able to reverse the chemical and physical changes that occur prior to the spawning act and survive to spawn a second and even a rare third time.

Spawning occurs when the doe or hen steelhead locates a suitable gravel area at the tailout of a pool. Turning her body in a sygmoid shape she snaps her tail upwards sucking the gravel out from its bed where the current will take it downstream. She repeats this a number of times in one location and then spawns between 500 and 2000 eggs in this first depression. The male, or buck, spawns his sperm at the same time, knowing from the excitement of the doe that she is spawning. Often two or more male steelhead will spawn at that same moment beside the doe. After the first spawn the doe moves upstream and once again using the sygmoid body shape she prepares another depression for a second spawn. The gravel from the second depression drifts downstream to cover the first spawning. This process is repeated until the doe has spawned her approximate 6000 eggs.

|

|

|

Chrome bright steelhead are easily caught with a variety of flies.

|

After spawning, steelhead are refereed to as kelts. In their emaciated state they drift downstream often feeding voraciously on any foods available. Their's is a race to reach the ocean food and many do not survive at this time. But, for those that do, the ocean offers a smorgasbord of feed and the salt water quickly mends the infections and sores that were sustained while they were in fresh water.

The life history of the steelhead is a fascinating story. It is a journey in a watery medium which is only now becoming unravelled as scientists discover more and more about this valuable resource. In my recent book, "Salgair, a Steelhead Odyssey," Hancock House, 1997, I detail the life history and odyssey of one steelhead's journey. I highly recommend it for the readers who wish detailed information about this majestic trophy trout. The steelhead is a true barometer of the health of watersheds and of the ocean. Their journey is a life long odyssey full of fascination and adventure.

"The End"

© Copyright Barry M. Thornton

Barry M. Thornton

|