BC Outdoor Odyssey

"An Odyssey or a Migration"

with Barry M. Thornton

I have always had a deep interest in wildlife

activity. This is intensified in the fall when annual

migrations begin for they give me a chance to observe

migrating wildlife in great numbers. One experience I

will never forget occurred when I first entered

university. I had registered in a natural science class

and was eagerly looking forward to learning more about

wildlife migrations. You can well imagine my astonishment

when the professor provided the following explanation for

bird migrations; "Birds migrate because their

parents migrated, and, their parents migrated because

their parents migrated". It was hardly the

scientific explanation that I expected or wanted. But,

since then, as I have become aware of ice ages, ocean

currents, jet streams, seasonal changes, photoperiodism

(light), imprinting, magnetite (a cell substance), the

earth's magnetic field and many other factors which

affect migration, I have also come to appreciate that the

professor's explanation was based upon genetic

inheritance, experience and as yet, many further

undiscovered factors. Yes, I too have come to realize

that birds migrate because their parents migrated.

Migration is the annual population shift of mammals

and birds

usually in response to seasonal changes. Light

(photoperiodism) rather than climate appears to be the

major triggering factor which makes birds begin their

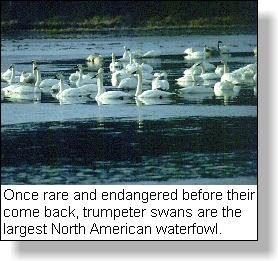

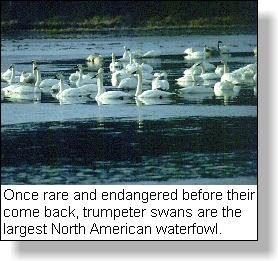

seasonal travels. One very dramatic B.C. waterfowl

example is the annual flights of the Trumpeter

Swans. Small family flocks can be predicted to first

appear after the middle of October. Flocks of these, the

largest North American waterfowl, appear in great numbers

through November and during the winter. B.C. coastal

estuaries and marine climate regions like Vancouver Island

winter the largest Pacific flyway concentration of

Trumpeter Swans, a bird that was once listed as rare and

endangered.

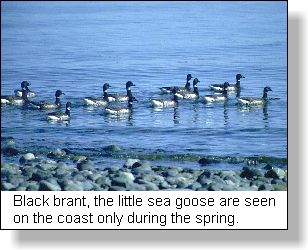

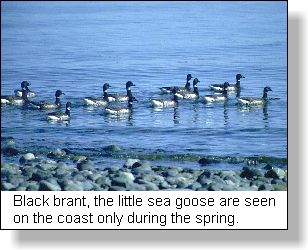

Bird

migration often has interesting seasonal adjustments. The

small sea goose, the Black Brant,

migrates north through the Strait of

Georgia and is a striking yet commonly seen coastal

bird beginning each April. However, in the autumn, Black

Brant migrate south along the outer coast, almost along

the continental shelf until they reach the Olympic

Peninsula in Washington state. None travel south in the

Strait of Georgia, the route they used in their spring

northerly migration. Why? Because this is the ancient

route of their parents. Bird

migration often has interesting seasonal adjustments. The

small sea goose, the Black Brant,

migrates north through the Strait of

Georgia and is a striking yet commonly seen coastal

bird beginning each April. However, in the autumn, Black

Brant migrate south along the outer coast, almost along

the continental shelf until they reach the Olympic

Peninsula in Washington state. None travel south in the

Strait of Georgia, the route they used in their spring

northerly migration. Why? Because this is the ancient

route of their parents.

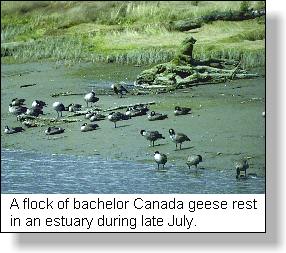

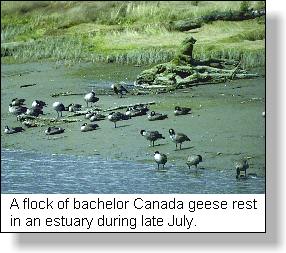

Waterfowl migration for many species occurs when the

young are capable of long distance flying. This is the

case with Trumpeter swans. It is also the situation with Canada

Geese and other geese species who begin to be heard

in September. Often long skeins or 'V' flocks can be

watched in the late summer blue skies. Why then, you may

ask, are there large flocks of Canada Geese arriving in

mid summer. The answer relates to the sexual maturity of

these birds. These early birds are in fact 'bachelor'

flocks composed of sexually immature geese of from one to

three years in age. These are not the family flocks of

mature adults and young of the year which have to wait

until the young are capable of long distance flying.

Geese do not mate until they are four years old and then,

they will mate for life with both parents sharing equally

in the raising of the annual brood of goslings.

Bird migration is not just a seasonal north-south

movement. Many ducks like scooters will nest in the

interior of the province and merely move to the coast for

the winter, performing an east-west migration.

In many

cases there is also vertical migration from higher

mountain ranges to valley bottoms as is performed by the

province's official bird, the Steller's Jay. Then there

is that oddity, the Blue Grouse, who migrates in reverse

by moving down the mountain in the spring to nest and

then travels up the mountain in the fall to the

sub-alpine areas where it winters feeding on the needles

of coniferous trees. In many

cases there is also vertical migration from higher

mountain ranges to valley bottoms as is performed by the

province's official bird, the Steller's Jay. Then there

is that oddity, the Blue Grouse, who migrates in reverse

by moving down the mountain in the spring to nest and

then travels up the mountain in the fall to the

sub-alpine areas where it winters feeding on the needles

of coniferous trees.

Mammals also migrate in many ways. Their movement is

also based upon light but it is affected also by changing

seasonal weather patterns. Ungulates like caribou

and elk

may travel long distances from summer pastures high in

watershed mountain slopes to timbered valley bottoms. On

the other hand sheep

and goats

travel up mountains in the winter seeking snow blown

slopes where they can feed, and, as protection from

wolves and other predators.

One misnomer that is in common use is to refer to the

return of salmon as a migration. In actual fact it is an

odyssey, a long wandering journey rather than the

seasonal shift from one location to another. The salmon

odyssey is a term I prefer for it conjures up an

impressive life journey. Some salmon, including steelhead, will

take up to five, six or even seven years to travel the

open Pacific Ocean before they return to spawn. We know

that all five west coast Pacific Salmon species die

following spawning adding their vital nutrients to the

stream to nourish hatching fry. Steelhead however, will

often survive and complete a second and even third

journey out to the open ocean then back to their natal

stream.

A migration

or an odyssey? British Columbians have an unique

opportunity to watch many wildlife species in their

annual movements from one location to another. To be so

fortunate to observe the behaviour of wildlife in a

province which has our country's greatest variety is a

fascinating, intriguing and enchanting experience. When

next you hear the call of the goose; or, see the blow

from a whale; or, watch struggling salmon in a stream;

or, provide winter bird feed for those sassy Steller's

jays in your backyard, remember that until scientists can

provide a definitive answer to migration, they are there

because their parent's were there. A migration

or an odyssey? British Columbians have an unique

opportunity to watch many wildlife species in their

annual movements from one location to another. To be so

fortunate to observe the behaviour of wildlife in a

province which has our country's greatest variety is a

fascinating, intriguing and enchanting experience. When

next you hear the call of the goose; or, see the blow

from a whale; or, watch struggling salmon in a stream;

or, provide winter bird feed for those sassy Steller's

jays in your backyard, remember that until scientists can

provide a definitive answer to migration, they are there

because their parent's were there.

© Copyright Barry M. Thornton

Barry M. Thornton

|

Bird

migration often has interesting seasonal adjustments. The

small sea goose, the

Bird

migration often has interesting seasonal adjustments. The

small sea goose, the  In many

cases there is also vertical migration from higher

mountain ranges to valley bottoms as is performed by the

province's official bird, the Steller's Jay. Then there

is that oddity, the Blue Grouse, who migrates in reverse

by moving down the mountain in the spring to nest and

then travels up the mountain in the fall to the

sub-alpine areas where it winters feeding on the needles

of coniferous trees.

In many

cases there is also vertical migration from higher

mountain ranges to valley bottoms as is performed by the

province's official bird, the Steller's Jay. Then there

is that oddity, the Blue Grouse, who migrates in reverse

by moving down the mountain in the spring to nest and

then travels up the mountain in the fall to the

sub-alpine areas where it winters feeding on the needles

of coniferous trees. A migration

or an odyssey? British Columbians have an unique

opportunity to watch many wildlife species in their

annual movements from one location to another. To be so

fortunate to observe the behaviour of wildlife in a

province which has our country's greatest variety is a

fascinating, intriguing and enchanting experience. When

next you hear the call of the goose; or, see the blow

from a whale; or, watch struggling salmon in a stream;

or, provide winter bird feed for those sassy Steller's

jays in your backyard, remember that until scientists can

provide a definitive answer to migration, they are there

because their parent's were there.

A migration

or an odyssey? British Columbians have an unique

opportunity to watch many wildlife species in their

annual movements from one location to another. To be so

fortunate to observe the behaviour of wildlife in a

province which has our country's greatest variety is a

fascinating, intriguing and enchanting experience. When

next you hear the call of the goose; or, see the blow

from a whale; or, watch struggling salmon in a stream;

or, provide winter bird feed for those sassy Steller's

jays in your backyard, remember that until scientists can

provide a definitive answer to migration, they are there

because their parent's were there.