B.C. OUTDOOR ODYSSEY

Pacific herring, a keystone species.

with Barry M. Thornton

In

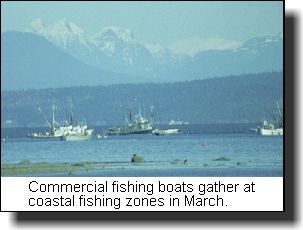

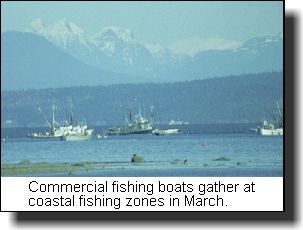

recent years, a concentrated human migration during mid March, the

visit of the annual herring commercial fleet, has provided a sure

sign of spring in many B.C. coastal areas. These fishers are the harbinger

of herring, a species so important to our west coast that they are

referred to as a keystone species, one upon which our west coast marine

environment and related species depend. In

recent years, a concentrated human migration during mid March, the

visit of the annual herring commercial fleet, has provided a sure

sign of spring in many B.C. coastal areas. These fishers are the harbinger

of herring, a species so important to our west coast that they are

referred to as a keystone species, one upon which our west coast marine

environment and related species depend.

Herring are one of those fascinating wildlife species who rely upon

vast numbers and schooling for survival. They have no sharp spines

and no poisonous fins like our many rockfish species for protection.

They are not fast and streamlined like salmon species and therefore

cannot escape predators with flight. It seems that their role is to

be the breadbasket species for most marine mammals and fish species.

Not an envious position, but, one which is vital to the health of

our Pacific coast's aquatic environment. I have often told my fishing

partners that, above all else, when I return in my next life, I pray

that it will not be as a herring.

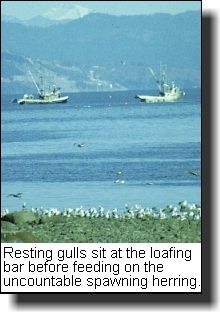

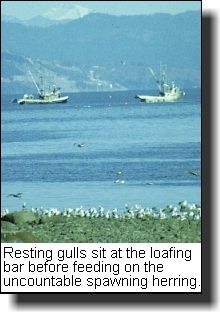

It

has been interesting these past few years to watch the 'herring furore'

in coastal waters. Vast fleets of highly specialized commercial fishing

vessels accompanied by white skies of sea gulls have been a common

sight in some communities. As well, new predators have entered the

fray in these 90's, herds of sea lions and seals. Sadly, when these

efficient marine predators have been satiated with herring, they have

turned on the few returning winter steelhead, decimating runs of these

now rare sports fish. In fact, so rare are these steelhead, that,

contrary to Fish & Wildlife provincial policy, some river species

like the Puntledge river winter steelhead have had the male sperm

'gene banked' in a process called cryopreservation for fear of their

extinction. It

has been interesting these past few years to watch the 'herring furore'

in coastal waters. Vast fleets of highly specialized commercial fishing

vessels accompanied by white skies of sea gulls have been a common

sight in some communities. As well, new predators have entered the

fray in these 90's, herds of sea lions and seals. Sadly, when these

efficient marine predators have been satiated with herring, they have

turned on the few returning winter steelhead, decimating runs of these

now rare sports fish. In fact, so rare are these steelhead, that,

contrary to Fish & Wildlife provincial policy, some river species

like the Puntledge river winter steelhead have had the male sperm

'gene banked' in a process called cryopreservation for fear of their

extinction.

Herring have a fascinating life cycle. The average female herring

spawns 20,000 eggs while the male herring spawns millions of minute

sperm. While standing on a coastal bluff overlooking the Strait of

Georgia during a March spawn, I was astounded at the vast hectares

of milky white water along the beach, opaque and creamy from the enormous

spawn. It was impossible to even guess the incredible numbers of herring

required to create this unique sight.

Unlike

salmon who die after spawning, herring reach maturity after three

years and, will usually spawn every year afterwards until they reach

'old' age at 8 or 10 years. Also, unlike salmon, herring do not necessarily

return to their natal site to spawn ( salmon return to their home

stream to spawn) but, rather, according to the Department of Fisheries

and Oceans; "They quite commonly spawn in one particular location

for several years, switch to another site to spawn for a number of

years and then return to the original location as much as a decade

later. The reason for this phenomenon is unclear but may be related

to localized variations in environmental conditions." Unlike

salmon who die after spawning, herring reach maturity after three

years and, will usually spawn every year afterwards until they reach

'old' age at 8 or 10 years. Also, unlike salmon, herring do not necessarily

return to their natal site to spawn ( salmon return to their home

stream to spawn) but, rather, according to the Department of Fisheries

and Oceans; "They quite commonly spawn in one particular location

for several years, switch to another site to spawn for a number of

years and then return to the original location as much as a decade

later. The reason for this phenomenon is unclear but may be related

to localized variations in environmental conditions."

During

the actual spawning process females usually discharge sticky eggs

onto living plants such as eelgrass, rockweed and kelp. It has been

estimated that one square inch of seaweed may be covered by as many

as 1000 transparent eggs. Depending upon water temperature, hatching

into a larval stage occurs in 2 to 3 weeks. Surprisingly, the 1/2

cm long larvae bear little resemblance to the adult fish. They lack

scales, the head and black eyes are greatly enlarged and, they can

barely swim. Mortality is greatest at this stage and may be as high

as 99%. During

the actual spawning process females usually discharge sticky eggs

onto living plants such as eelgrass, rockweed and kelp. It has been

estimated that one square inch of seaweed may be covered by as many

as 1000 transparent eggs. Depending upon water temperature, hatching

into a larval stage occurs in 2 to 3 weeks. Surprisingly, the 1/2

cm long larvae bear little resemblance to the adult fish. They lack

scales, the head and black eyes are greatly enlarged and, they can

barely swim. Mortality is greatest at this stage and may be as high

as 99%.

During the next 2 months a gradual metamorphosis takes place. By

the time the fish has grown to a length of 4 cm it's outward appearance

has changed into that of a miniature adult herring. Schooling begins

and the young herring, are usually found in the shallow water of bays

and inlets and near kelp beds during the summer months. It is estimated

that only one herring from 10,000 eggs matures to adult size to repeat

the spawning act of the parents.

Adult

herring are migratory in nature although a few minor stocks remain

within the confines of coastal bays and inlets. Herring spawned in

the Strait of Georgia migrate to the banks off the lower west coast

of Vancouver Island. They leave these rich offshore feeding grounds

in the late fall or winter and migrate back to inshore waters to spawn

in March and April. Adult

herring are migratory in nature although a few minor stocks remain

within the confines of coastal bays and inlets. Herring spawned in

the Strait of Georgia migrate to the banks off the lower west coast

of Vancouver Island. They leave these rich offshore feeding grounds

in the late fall or winter and migrate back to inshore waters to spawn

in March and April.

According to the Department of Fisheries & Oceans (DFO), the roe

herring fishery in the Strait of Georgia, "is directed on migratory

stocks" with a management strategy, "to ensure that 80% of the fish

spawn". Further, they state, "The Strait of Georgia herring stock

has experienced above average recruitment in five of the last seven

years resulting in near historically high levels of abundance. A total

of 131 kilometres of herring spawn was measured in the Strait of Georgia

in 1996."

This past March, the Strait of Georgia commercial herring fishery

was confined to Area 14 with most catches occurring in waters north

of the Denman and Hornby Gulf islands. DFO Fisheries Officers reported

that there were 63 Seine vessels in the fleet and 328 Gillnet vessels.

The seine fleet had a one hour and 29 minute opening on March 4th

and made a 'hail' catch of 9410 tons of herring. The gill net fleet

had a 7 hour opening on March 19th and finished with a 'hail' catch

of 6294 tons of herring. A conservative estimated cash value of this

catch, at approximately $2500 a ton, is over $30 million. There can

be no doubt that this silver bounty is one of our west coast's most

unique and precious assets.

While

herring are a valuable economic species, there is repeated concern

expressed about this commercial fishery and the effect it has on the

ecology of coastal areas. Will the loss of biomass affect the saltwater

environment like the loss of spawning salmon biomass affects the growth

of newborn salmon? Is this the reason why some salmon species like

coho no longer use the Strait of Georgia as a growing zone? Only time

will tell, but, what is known is that the herring is a west coast

keystone species and must receive intensive study and a conservative

management strategy. While

herring are a valuable economic species, there is repeated concern

expressed about this commercial fishery and the effect it has on the

ecology of coastal areas. Will the loss of biomass affect the saltwater

environment like the loss of spawning salmon biomass affects the growth

of newborn salmon? Is this the reason why some salmon species like

coho no longer use the Strait of Georgia as a growing zone? Only time

will tell, but, what is known is that the herring is a west coast

keystone species and must receive intensive study and a conservative

management strategy.

More Photos

Photo1 | Photo2

| Photo3 | Photo4

© Copyright Barry M. Thornton

Barry M. Thornton

|

In

recent years, a concentrated human migration during mid March, the

visit of the annual herring commercial fleet, has provided a sure

sign of spring in many B.C. coastal areas. These fishers are the harbinger

of herring, a species so important to our west coast that they are

referred to as a keystone species, one upon which our west coast marine

environment and related species depend.

In

recent years, a concentrated human migration during mid March, the

visit of the annual herring commercial fleet, has provided a sure

sign of spring in many B.C. coastal areas. These fishers are the harbinger

of herring, a species so important to our west coast that they are

referred to as a keystone species, one upon which our west coast marine

environment and related species depend. It

has been interesting these past few years to watch the 'herring furore'

in coastal waters. Vast fleets of highly specialized commercial fishing

vessels accompanied by white skies of sea gulls have been a common

sight in some communities. As well, new predators have entered the

fray in these 90's, herds of sea lions and seals. Sadly, when these

efficient marine predators have been satiated with herring, they have

turned on the few returning winter steelhead, decimating runs of these

now rare sports fish. In fact, so rare are these steelhead, that,

contrary to Fish & Wildlife provincial policy, some river species

like the Puntledge river winter steelhead have had the male sperm

'gene banked' in a process called cryopreservation for fear of their

extinction.

It

has been interesting these past few years to watch the 'herring furore'

in coastal waters. Vast fleets of highly specialized commercial fishing

vessels accompanied by white skies of sea gulls have been a common

sight in some communities. As well, new predators have entered the

fray in these 90's, herds of sea lions and seals. Sadly, when these

efficient marine predators have been satiated with herring, they have

turned on the few returning winter steelhead, decimating runs of these

now rare sports fish. In fact, so rare are these steelhead, that,

contrary to Fish & Wildlife provincial policy, some river species

like the Puntledge river winter steelhead have had the male sperm

'gene banked' in a process called cryopreservation for fear of their

extinction.  Unlike

salmon who die after spawning, herring reach maturity after three

years and, will usually spawn every year afterwards until they reach

'old' age at 8 or 10 years. Also, unlike salmon, herring do not necessarily

return to their natal site to spawn ( salmon return to their home

stream to spawn) but, rather, according to the Department of Fisheries

and Oceans; "They quite commonly spawn in one particular location

for several years, switch to another site to spawn for a number of

years and then return to the original location as much as a decade

later. The reason for this phenomenon is unclear but may be related

to localized variations in environmental conditions."

Unlike

salmon who die after spawning, herring reach maturity after three

years and, will usually spawn every year afterwards until they reach

'old' age at 8 or 10 years. Also, unlike salmon, herring do not necessarily

return to their natal site to spawn ( salmon return to their home

stream to spawn) but, rather, according to the Department of Fisheries

and Oceans; "They quite commonly spawn in one particular location

for several years, switch to another site to spawn for a number of

years and then return to the original location as much as a decade

later. The reason for this phenomenon is unclear but may be related

to localized variations in environmental conditions." During

the actual spawning process females usually discharge sticky eggs

onto living plants such as eelgrass, rockweed and kelp. It has been

estimated that one square inch of seaweed may be covered by as many

as 1000 transparent eggs. Depending upon water temperature, hatching

into a larval stage occurs in 2 to 3 weeks. Surprisingly, the 1/2

cm long larvae bear little resemblance to the adult fish. They lack

scales, the head and black eyes are greatly enlarged and, they can

barely swim. Mortality is greatest at this stage and may be as high

as 99%.

During

the actual spawning process females usually discharge sticky eggs

onto living plants such as eelgrass, rockweed and kelp. It has been

estimated that one square inch of seaweed may be covered by as many

as 1000 transparent eggs. Depending upon water temperature, hatching

into a larval stage occurs in 2 to 3 weeks. Surprisingly, the 1/2

cm long larvae bear little resemblance to the adult fish. They lack

scales, the head and black eyes are greatly enlarged and, they can

barely swim. Mortality is greatest at this stage and may be as high

as 99%.  Adult

herring are migratory in nature although a few minor stocks remain

within the confines of coastal bays and inlets. Herring spawned in

the Strait of Georgia migrate to the banks off the lower west coast

of Vancouver Island. They leave these rich offshore feeding grounds

in the late fall or winter and migrate back to inshore waters to spawn

in March and April.

Adult

herring are migratory in nature although a few minor stocks remain

within the confines of coastal bays and inlets. Herring spawned in

the Strait of Georgia migrate to the banks off the lower west coast

of Vancouver Island. They leave these rich offshore feeding grounds

in the late fall or winter and migrate back to inshore waters to spawn

in March and April. While

herring are a valuable economic species, there is repeated concern

expressed about this commercial fishery and the effect it has on the

ecology of coastal areas. Will the loss of biomass affect the saltwater

environment like the loss of spawning salmon biomass affects the growth

of newborn salmon? Is this the reason why some salmon species like

coho no longer use the Strait of Georgia as a growing zone? Only time

will tell, but, what is known is that the herring is a west coast

keystone species and must receive intensive study and a conservative

management strategy.

While

herring are a valuable economic species, there is repeated concern

expressed about this commercial fishery and the effect it has on the

ecology of coastal areas. Will the loss of biomass affect the saltwater

environment like the loss of spawning salmon biomass affects the growth

of newborn salmon? Is this the reason why some salmon species like

coho no longer use the Strait of Georgia as a growing zone? Only time

will tell, but, what is known is that the herring is a west coast

keystone species and must receive intensive study and a conservative

management strategy.